By Julian Borrmann

Before it became a vacation hotspot, St. Petersburg was a wartime stronghold. With more than 100,000 military trainees flooding the city, 62 local hotels were converted into barracks and hospitals. This massive influx reshaped the community, as many soldiers and their families remained in Florida long after the war ended.

Rui Farias, a local historian specializing in war history, recalled interviewing a student at St. Petersburg High School when World War II broke out in the 1940s.

“He told me it was like living in a war film,” Farias said. “Every day, he’d walk home from school and watch planes dogfighting in the sky, shooting blanks during training. He could even hear live ammunition striking the beaches.”

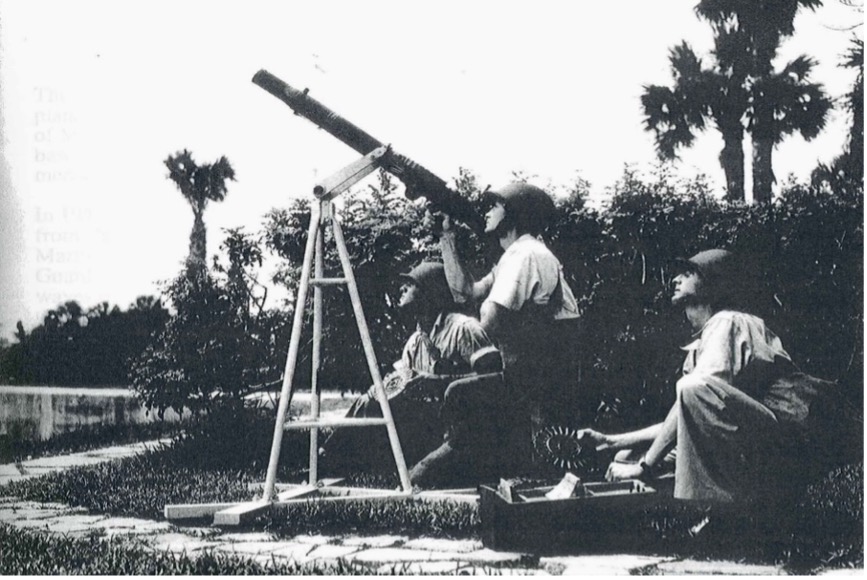

According to Farias, both trainees and officers practiced a variety of warfare maneuvers throughout the city, including aerial dogfights, anti-aircraft weaponry drills and more.

“Depending on where you were in the city — whether on the south side or near Pinellas Point — you could hear them bombing Egmont Key,” Farias said.

Many residents, including veterans and service members, are unaware of the significant impact World War II had on St. Petersburg, which brought major changes and challenges to the community in the early 1940s.

Army veteran Joseph Schern, who served in the Iraq War, was stunned to learn about this hidden chapter of the city’s past. Having lived in Pinellas County for 26 years, he said he found it bizarre that he had never heard about St. Petersburg’s role in the war.

“You’ve got to be kidding me,” Schern said. “You always hear about places like Norfolk or San Diego when it comes to military history, but here? I had no idea. That’s something people should be talking about more.”

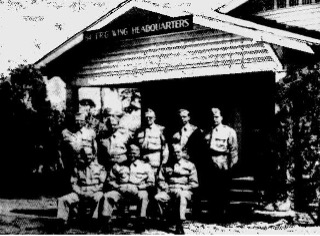

St. Petersburg was home to one of the Army Air Force’s major basic training centers of its time. The base played a crucial role in training and preparing young men for the war, operating briefly from 1942 to 1943 before closing its doors.

The influx of trainees was pushed into every hotel in the city, significantly increasing the population, but also leading to a housing shortage as families searched for suitable accommodations.

Many young servicemen brought their wives and children with them to St. Petersburg during World War II. As the war went on, some never returned home, leaving behind widows and families in search of housing.

Historic neighborhoods such as Old Northeast and Historic Uptown, known today for their century-old homes and apartment buildings, saw major changes during the 1940s.

Many large single-family homes were divided into multi-unit residences to accommodate the influx.

“These four- or five-bedroom homes—many of them were turned into boarding houses,”Farias said.

Even today, he said, the impact is visible. “When you drive up and down these brickroads, you’ll see older buildings that look too big to be a house but are now apartments,” Farias said. “At one time, they were probably a single-family home.”

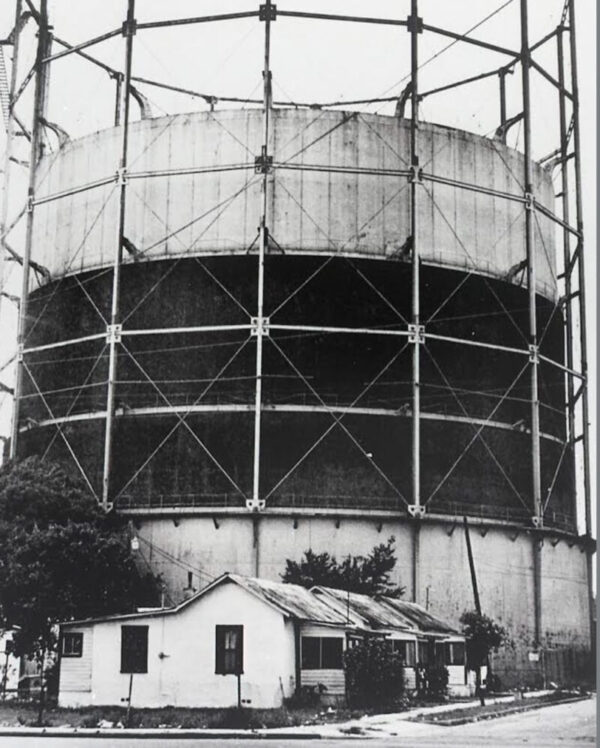

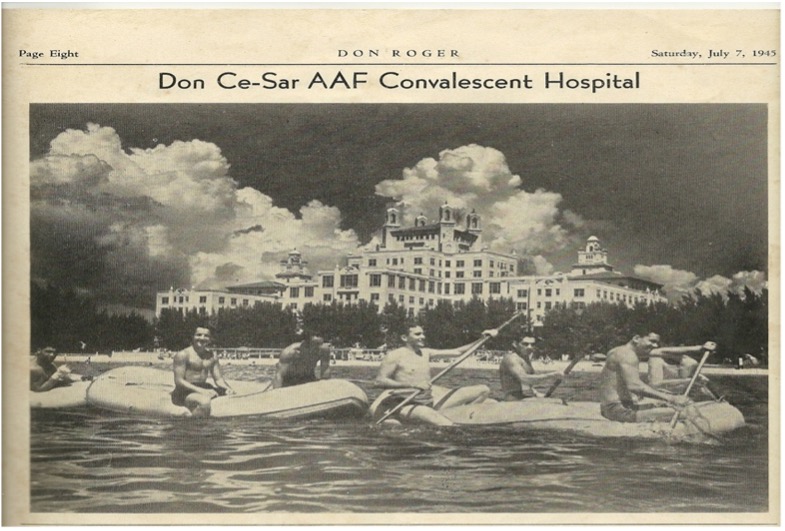

The Department of War, presently known as the Department of Defense, and city officials went to great lengths to ensure soldiers had proper accommodations, even though it posed challenges for the local community. The AAF took over 452 hotels across the country, including 62 in St. Petersburg alone — one of which was the Don CeSar hotel.

From 1942 to 1944, the luxury “Pink Palace” was transformed into a subbase hospital and convalescent center for soldiers, one of many hotels providing medical care, rehabilitation and rest for servicemen wounded overseas.

“I mean, you hear ghost stories about old hospitals all the time, right,” former U.S. Marine Corey Stuempert said. “Now knowing the Don CeSar was actually a military hospital, it makes you wonder if some of those stories are tied to the soldiers who were there.”

Similar to Schern, Stuempert has been a St. Petersburg resident for years and never knew or heard of the crucial role the community and city played during WWII.

Meanwhile, the Vinoy Resort & Golf Club, Autograph Collection closed its doors to the public in July 1942 and was repurposed as a training center for the United States Maritime Service, housing military cooks and bakers preparing to serve overseas.

Despite housing inconveniences, some businesses—particularly theaters, bars and restaurants—thrived downtown. If there was one thing these young men and their ladies loved, it was having a good time whenever they could. After a long day of training, they were also in need of plenty of food.

“The owner of Mastry’s Bar and Grill allegedly said he made more money from 1942 to 1945 than in all the years after the war,” Farias said, noting how frequently these men visited local bars during that time.

After the war ended in late 1945, most hotels closed their doors again, remodeling their interiors to better accommodate the public and resume operations for tourists, as did other businesses in town.

Today, the remnants of St. Petersburg’s wartime role may be hidden beneath renovations and timeworn facades, but their influence lingers. The city’s streets, buildings and communities still echo the resilience of those who trained, served and sacrificed in the community.