By Emilie Bell and Tori Foltz

The City of St. Petersburg’s 70-year-old wastewater facilities struggled during Hurricanes Helene and Milton, as water inundated underground pipes and the low-lying plants near the city’s waterways.

Claude Tankersley, the City of St. Petersburg’s Public Works Administrator, works with five of the city’s departments. Tankersley oversees Stormwater, Pavement and Traffic Operations, Water Resources and the Office of Sustainability and Resilience.

Tankersley said 2024 was an “extremely unusual year.” The city’s plants were built in the 1950s and had never withstood such unprecedented circumstances.

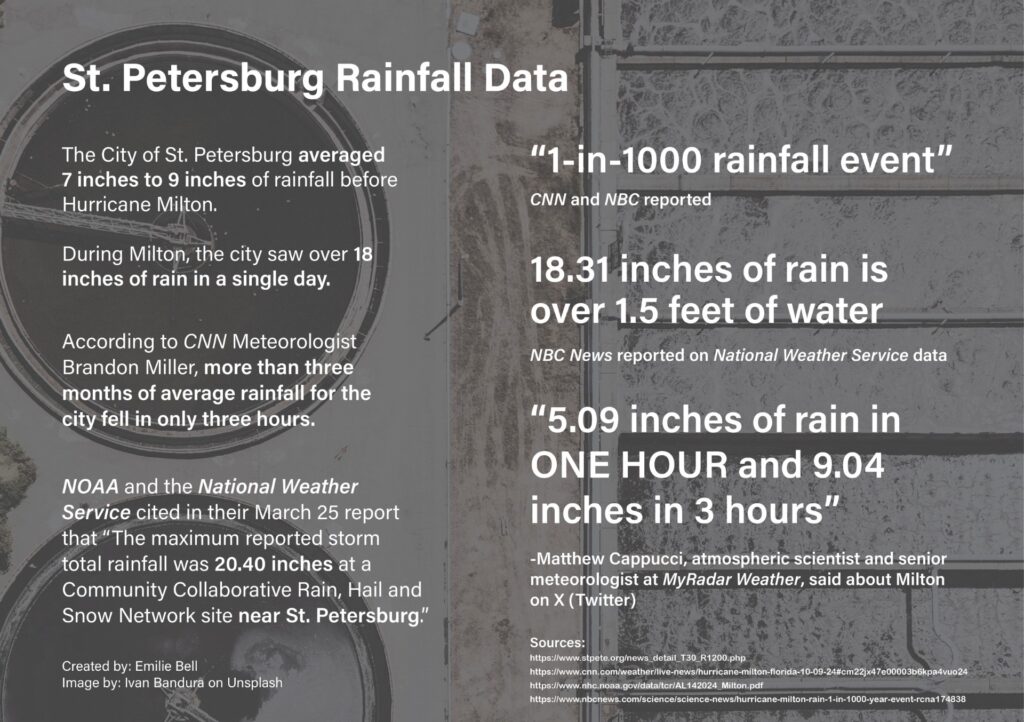

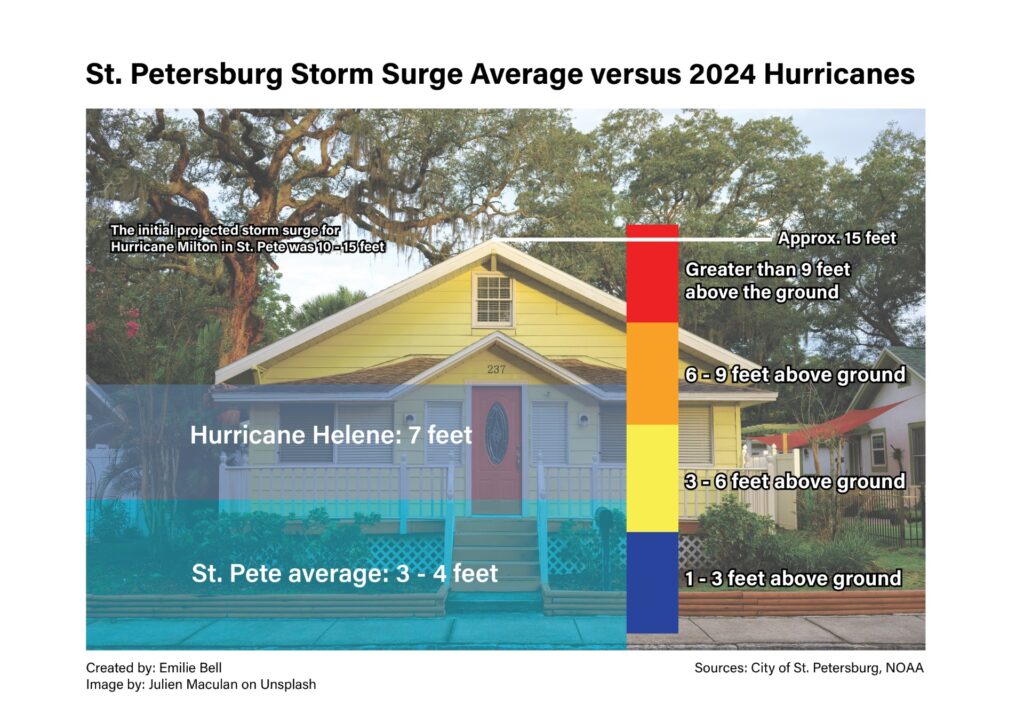

“For 100 years, we had seen rainfall in these amounts [7 to 9 inches] and storm surges in these amounts [3 to 4 feet],” Tankersley said. “And so, our system was built assuming, you know, they had the protection for rainfall [and storm surge] in these amounts.”

During Hurricane Milton, St. Petersburg received over 18 inches of rain in a single day, according to Tankersley. The city’s previous data, from decades prior, showed rainfall in the range of 7 to 9 inches in a single day.

“That’s two to three times more in one day than we had ever seen before in the history of St. Petersburg, ever, as long as we’ve been keeping records,” Tankersley said.

He said the same had occurred with the storm surge data, where decades ago the surges were around 3 to 4 feet. With Hurricane Helene, the city saw a surge of 7 feet.

Snell Isle resident, Ryan Bremner, stayed in his single-story home with his partner, Nikki Life, during Hurricane Helene. Bremner said that after the water began to come up beneath the floor, he and Life went to their neighbor’s house, a two-story home.

According to Bremner and Life, this was around 10-10:30 p.m. As they made their way through the flood waters, Life said it was dark, and they couldn’t see anything.

“The water was already over the manholes by [a few feet] at that point,” Life said.

After they crossed the street to reach higher ground, Bremner described the scene around them.

“I mean, it’s hard to describe because we looked out the window from the neighbor’s

house and there’s no street,” Bremner said. “There’s no yard. It’s all just flat black water. It’s kind of surreal.”

Seeing is Believing

Tankersley used the analogy of a house to illustrate how suddenly circumstances can change.

“Let’s say that you’re a young couple,” Tankersley said. “You haven’t got any children yet. You’ve got a house with two bedrooms and one bath. It’s perfect for you. It works for you. But then your situation changes. All of the sudden, you give birth to triplets. Now you need more than two bedrooms and one bath. You need a third bedroom, maybe a second bath, right? The situation changed. That’s what happened here at the city.”

What worked five to 10 years ago no longer worked for the wastewater facilities. The unprecedented output of water from Helene and Milton put a strain on the city’s plants. For almost 75 years, the plants had endured Tampa Bay’s extreme weather events.

Tankersley reflected on the challenge that, he claims, people are facing in society.

“The challenge is that there have been people in our society, in our culture, that have been warning of these things for a while,” Tankersley said. “But it’s one thing to be warned of something that has never happened versus seeing something happen and being like, ‘oh, wait a minute, yes it can.’”

He compared his reckless nature as a teenage driver to recent extreme weather events.

“People would warn me, ‘if you keep driving like that, you’re going to get in an accident,’” Tankersley said.

With the arrogance and naivety of being an 18-year-old, he brushed off those claims, as he had confidently been driving for two years. When he got into his first accident, he said he realized that those types of bad things actually can happen, just like severe weather events.

“I think now that people are seeing these extreme weather events that we’ve heard about, that have been easy to be, like, ‘that’s just a bunch of scientists crying wolf and whoopty doo,” Tankersley said. “Now it’s like, ‘oh wow, OK, it actually does happen.’”

The City’s Solutions

The city has implemented the Agile Resilience Plan, which is an effort to accelerate wastewater and stormwater-related projects, according to Tankersley. Many of these projects have been planned for 20 years in advance, but Tankersley said that the city lacks sufficient funding to finish them in a timely manner.

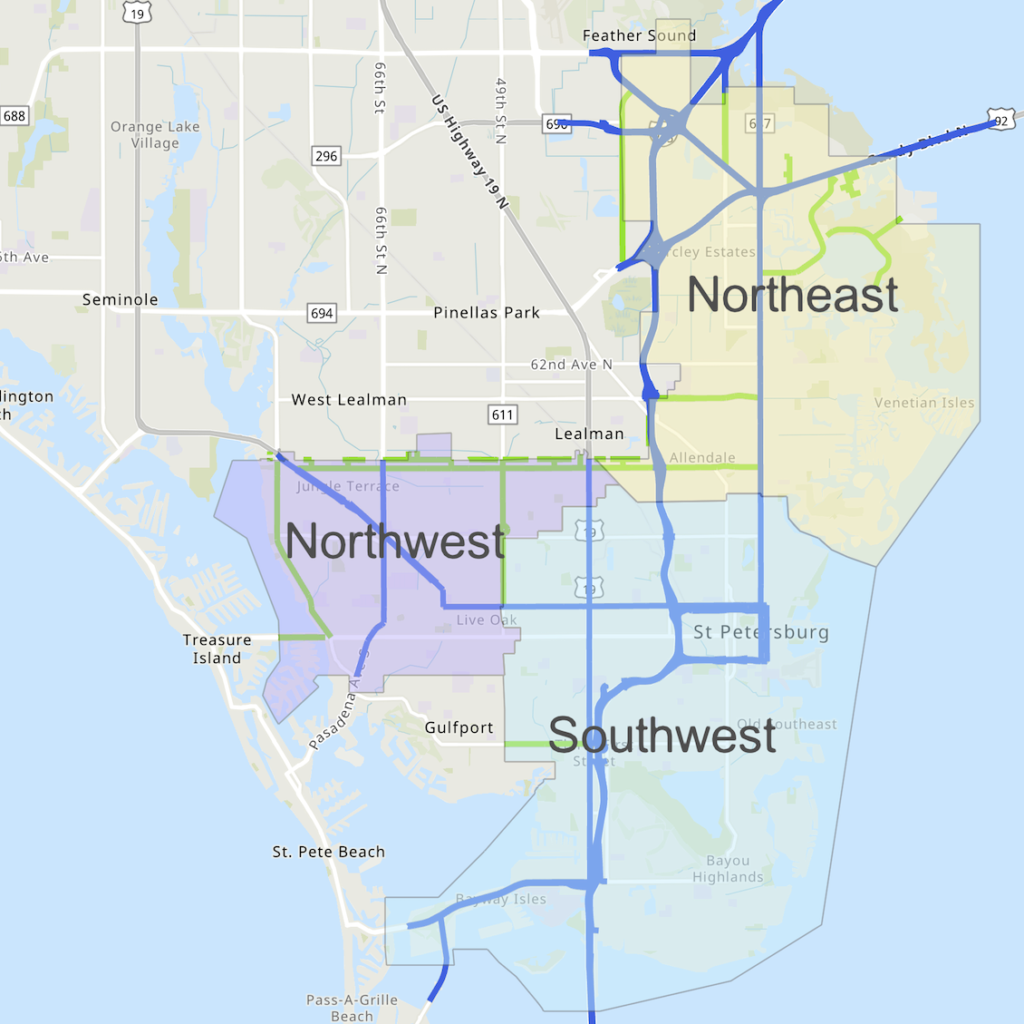

Situated around the city are three wastewater plants, all receiving sewage from the network of

uphill pipes, which output the treated water into the local waterways. Tankersley said the reclamation facility that received the brunt of the storm surge was the Northeast facility.

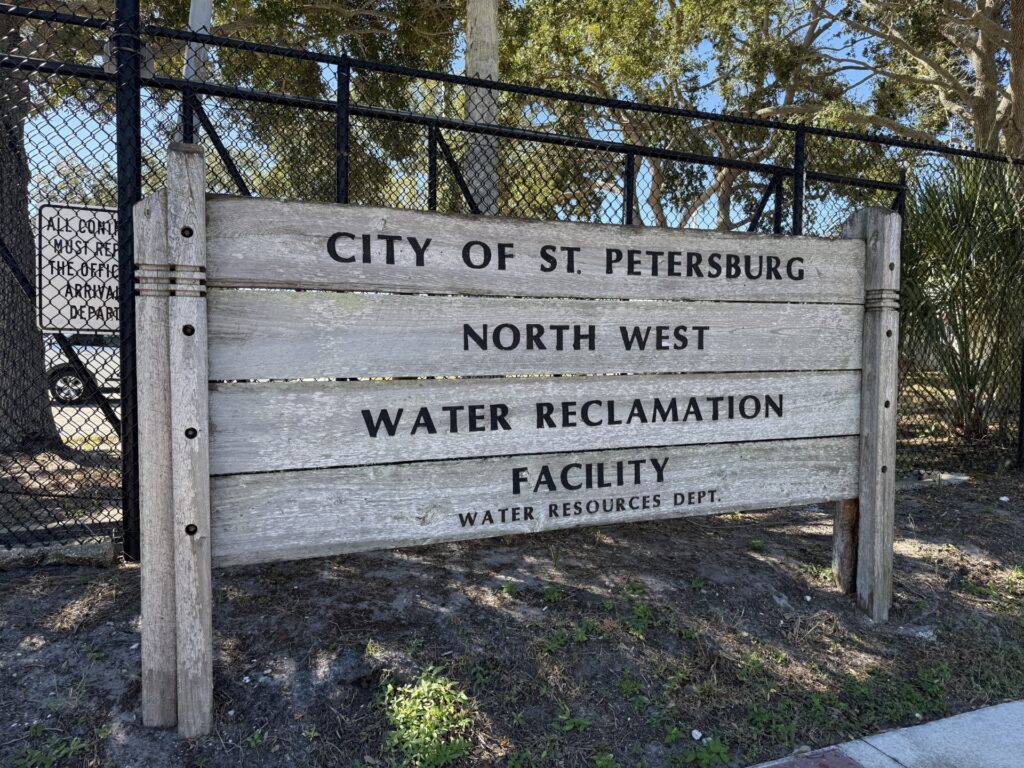

According to Tankersley, the Northwest facility, which receives sewage from St. Petersburg

Beach and Treasure Island, had a larger impact in terms of spills during the storms.

The Southwest plant is the second lowest reclamation facility regarding elevation and sea level, with the Northeast facility being the lowest.

With the plants being so close to the waterways, they sit in a flood zone.

So, what this plan is, is to try to help us find a way to accelerate those projects,” Tankersley said. “And the only way to accelerate those projects is to find more money. So that’s the real key to this plan, is working with the public to agree that we as the public, we’re going to pay more money in our annual utility bills and our annual taxes in exchange for you, the city, doing these projects sooner than you would have otherwise.”

In the coming years, the city will be raising the electrical equipment in the wastewater facilities 15 feet above sea level. Equipment that cannot be raised will be protected by building barriers, such as the AquaFence the city purchased recently.

Data For a Changing Climate

The Florida Flood Hub for Applied Research and Innovation was established in 2021 by Florida’s state legislature as a part of the Resilient Florida Program. The organization is based at the University of South Florida’s College of Marine Science, where they research environmental challenges in Florida. Their goal is to improve flood forecasting and inform science-based policy, planning and management.

Heidi Brockhaus is a scientific liaison for the Florida Flood Hub. Liaisons ensure the data reaches stakeholders and serve as a resource for anyone who has questions or concerns about the data.

The Florida Flood Hub studies sea level rise and extreme rainfall. Brockhaus said flooding is one of the biggest hazards in Florida.

In July, they released sea level rise estimates from 2000 to 2070. Based on the data, sea levels will rise from 16.9 to 21.8 inches by 2070.

Many areas around the state are seeing increased intensity of rainfall events. This puts a strain on stormwater systems because the more rain there is, the more capacity is needed to handle all that

water.

Brockhaus said with the increase in intense rainfall in Florida, it will be important for agencies to plan accordingly with the data.

“Looking ahead to flooding hazards over the coming decades, and trying to understand the magnitude of the change that’s coming and the likelihood, like how much sea level rise and how likely it is that that’s going to happen by a given amount of time, is really useful for local counties, municipalities and other agencies to plan and prepare,” Brockhaus said.

The Florida Flood Hub will continue to release data about environmental challenges in Florida.

County Municipalities Working Together

From 2016 to 2021, Pinellas County implemented the Wastewater/Stormwater Partnership, which was a joint initiative of the Pinellas County Board of County Commissioners and Pinellas County municipalities.

The initiative’s goal was to identify wastewater and stormwater solutions for the county. However, the partnership is not currently active.

According to Pinellas County Public Works, the county works in tandem with the municipalities in the surrounding area after a hurricane. However, each municipality is responsible for managing and maintaining its own systems. This includes seeking federal funds through the Federal Emergency Management Agency and the state.

In the future, residents may be facing a stormwater impact fee. According to the St. Pete Catalyst, St. Petersburg residents will experience a 17.5% stormwater rate increase this month after a 25% increase last year. Unlike several other cities in Florida, St. Petersburg lacks a stormwater-specific impact fee.

However, Florida Senate Bill 180, which went into effect on June 26, prohibits local governments from adopting more restrictive land-use and development regulations after a natural disaster. As a result, residents are unlikely to see stormwater impact fees until 2027.