By Emilie Bell and Tori Foltz

The recidivism rate in Florida—that is, reoffending citizens returning to jail or prison—is the fifth lowest in the country. Yet, Florida has the third-largest prison population, with over 87,000 people incarcerated. Reentry programs, designed to help recently released inmates, provide the necessary services for individuals to find their way back into society. These programs provide the foundation for “recent releases” needs while guiding them away from the path of recidivism.

The Tampa Bay region houses a number of organizations dedicated to reentry services. One program, Operation New Hope, serves St. Petersburg and Tampa. Their mission is to provide second chances to the prison population—their motto being “Second chances matter.”

Shawn Davis is the Ready4Release program manager at ONH St. Petersburg, which opened in June 2024. They operate out of Mount Zion Progressive Missionary Church, near the Warehouse Arts District. In his role, he works with the Department of Corrections to deliver pre-release services to facilities across the state. Davis works with 13 institutions along the West Coast and Central Florida. While visiting each institution, Davis pitches the program to qualifying inmates.

“When I have that conversation with them, I (try to let them) understand that they are not forgotten about,” Davis said. “That nobody wants to be remembered for the worst thing they’ve ever done; been accused of the worst thing they’ve ever done. We are organizations that care enough to give you a soft landing after a hard time.”

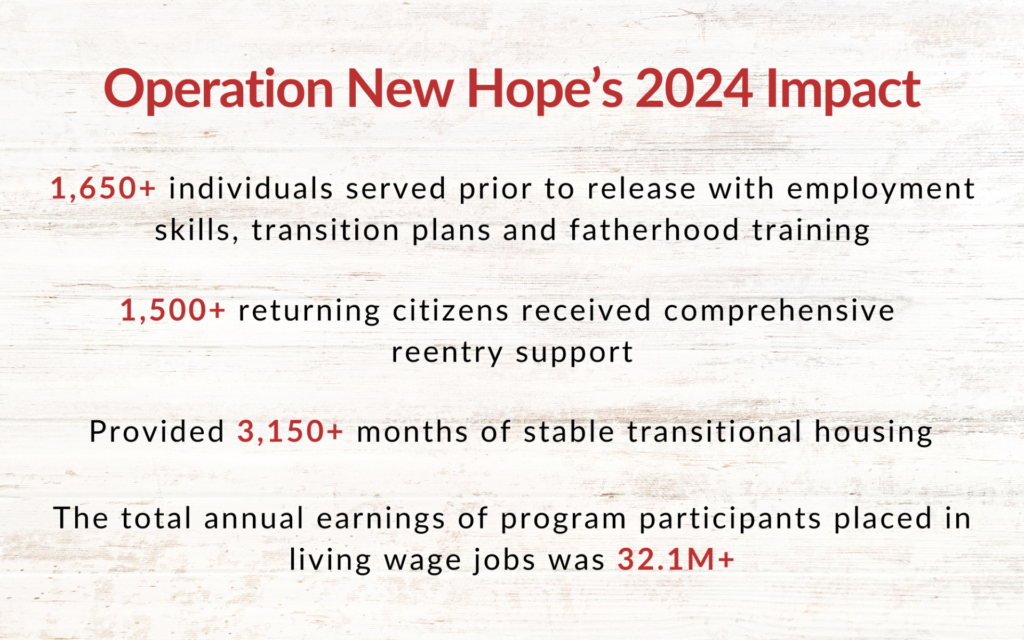

ONH was founded in 1999 with the mission to provide support and training to people impacted by the justice system by connecting them to the workforce, their families and communities.

The organization has six locations across the state, including Jacksonville, Orlando, Tampa, St. Petersburg, Space Coast and St. Augustine. ONH delivers services to 43 institutions in Florida.

In 2024, they served over 1,600 individuals across the state.

“We ultimately want to help as many people as we possibly can, pulling together as many resources as we can locally,” Davis said. “And the best way to do that is by showing proof that we do care about this type of population.”

At ONH, recently released inmates are referred to as “second chance citizens.” Davis refers to them as “clients.”

While working with his clients, he aims to reinforce that “it’s not about what you did, it’s about what you’re going to do.”

“One of the things they ask us when we first get hired is to define hope,” Davis said. “We also ask our clients prior to graduation, what’s their definition of hope? I think hope is the foundation for every tomorrow we’ll ever have. And what we hope is it’s going to either be better or not worse than the day we had before. I think that’s what we do—we inject that hope in the individuals.”

Initial challenges

Leaving correctional facilities and reentering society, second chance citizens face many adversities. The structure of ONH has considered the needs of someone recently released and facilitated that. They focus on housing, vital documentation, job training, clothing, meals and mental health services. ONH also helps second chance citizens who may have been incarcerated for over a decade and are unfamiliar with the technology of today.

With this comes the weight of social stigmatization, which affects them as an individual mentally and in the hiring process.

“I think what happens is people come against resistance coming out,” Davis said. “While they’re in the institution, (they’re like) ‘OK, this time I’m going to get it right. I’m not going to do any crimes.’ When they get out, they’re just treated like a criminal, even though they haven’t committed another crime. ‘I’ve done my time, but I got the Scarlet letter, and I can’t move on.’”

Davis uses an analogy, which he describes as “doctored up,” to explain why reentry programs are important. He tells his clients how to work through the system.

“If you’re a street pharmacist, it’s the easiest and most dangerous job in the world,” Davis said.

But there’s also that inherent risk of being arrested and going back to jail again. Davis presents another option to them.

“Don’t do the easiest job in the world,” Davis said. “Come out here and get this job, and you have to work your way up. But I’m telling you to work your way up with no skills, no understanding, no clothing, no tools, no support in trying to navigate almost a corporate structure from coming from the bureaucracy of an institution.”

Ready4Release Program

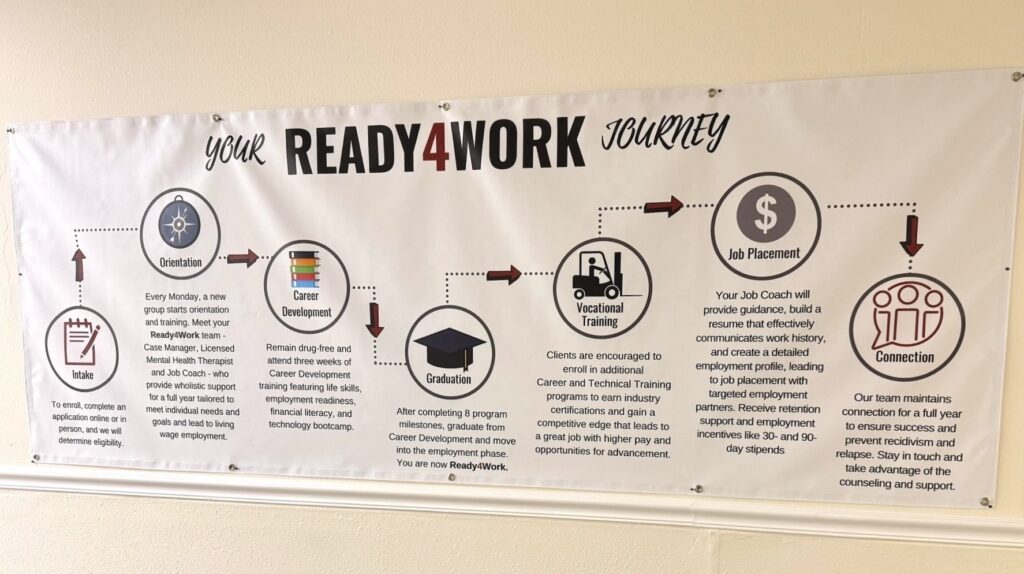

At the facilities, Davis meets with clients monthly during the 90 days before their release. Anyone who has been affected by the criminal justice system, resulting in incarceration, qualifies for Ready4Release. ONH does not take individuals with sexual offenses.

“We are given some leniency on charges, which allows for leadership and staff to take into consideration other factors, such as when did the charge happen, has there been pattern of them doing the same charge and the severity of the police report when available,” Davis said.

When Davis meets with potential clients, he tells them Ready4Release costs them four things: their participation, discipline, being substance-free and their old life.

“They have to let it go,” Davis said. “The old life is dead weight, and if they hold on to it, it’ll drag them back into this institution.”

Davis said the first 15 days are the most challenging part of the program. During the program, participants experience career development training. Here, they are also connected to a case manager, job coach and mental health therapist.

Ready4Release continues weekly, with program graduations happening every Friday. The graduation rate is between 82% and 85%.

According to the data that ONH follows, individuals who have somewhere to stay and access to clothes, food and money are less likely to commit a crime. Ready4Release covers those factors for the first 90 days.

“Our hope is, long before the 90 days, that we have gotten them employed with a provider in our areas, and that they can start rebuilding that chapter in their life,” Davis said.

Davis said ONH tries to walk them into this new chapter.

“I tell them to walk, because if you run, you’re likely to trip,” Davis said. “If you trip, you fall. If you fall, it’s likely the way things are set up is for you to come back to an institution.”

Case Management

When participants enter the program, they are connected to a case manager. The case manager will ensure they have all the vital documentation needed to get a job. When individuals get closer to their release date, they will at least have an ID—this can be attributed to Florida Licensing on Wheels. Davis explained that Florida identification buses go to institutions to help inmates who are close to their release dates obtain their identification.

But other documents tend to get misplaced, and it’s not guaranteed that a FLOW bus could assist individuals with their documentation.

If an individual cannot get their ID, their case manager sends a letter to the DMV, where they also request their birth certificate and Social Security card. These three documents are required for employment.

Their case manager will help them secure medical insurance for a year. They will assist with future planning as well.

“The case manager is going to help them work those plans out because they want to hear about what their goals are and try to map out a place to get there,” Davis said.

This includes finding ways to secure housing, transportation and preferably, a job with benefits.

Case managers work in tandem with pre-release program managers. Their job is to ensure that individuals have the resources they need to prevent recidivism.

Job Coaching

At ONH, job coaches connect with employers in the community and express the possible benefits of employing second chance citizens.

“They’ve gathered habits where they can get up early in the morning,” Davis said. “They work well in structure. A lot of them are really eager to get this next change in their life.”

Davis said the job coaches are very good at pacing individuals through the job search process. When speaking with clients, he emphasizes that they may start at an organization on a starting pay and work their way towards their goal.

Melissa Riggins is the workforce development coordinator for ONH in Jacksonville. She described the role of Ready4Work as removing barriers to employment. They help clients develop skills, confidence and support systems that Riggins said are necessary for them to “successfully reintegrate and thrive.”

As the workforce development coordinator, Riggins described her personal goals within the program.

“My goal is to meet each client where they are and guide them toward meaningful, sustainable employment,” Riggins said. “I focus on identifying their strengths, interests and career goals while addressing any barriers that may limit their success. Ultimately, I aim to empower clients with the tools, training, and support needed to achieve long-term stability and self-sufficiency.”

employment phase, job placement guidance and connection to the ONH team for a full year after the program to prevent recidivism. (Photo courtesy of Shawn Davis)

Riggins listed numerous roles that second chance citizens seek out during the Ready4Work program.

“Many second chance citizens gravitate toward careers that offer upward mobility, hands-on work and employers open to second-chance hiring,” Riggins said. “This often includes logistics, construction, manufacturing, transportation and service-based roles—though with the right support, clients can excel across many industries.”

Riggins said that ONH offers in-house and community training for its clients. There are a range of job training pathways, including: logistics and warehouse operations, construction and skilled trades, CDL and commercial driving, hospitality and customer service, manufacturing and production, healthcare support roles, maritime/seafarer training and basic computer skills and workplace readiness.

Riggins related second chances, one of ONH’s missions, to the job training program.

“‘Second chances matter’ means recognizing that people are more than their past and deserve the opportunity to rebuild their lives,” Riggins said. “In the workforce, this translates to creating fair access to employment, reducing stigma around hiring justice-involved individuals and valuing their potential.”

She said by offering someone a real second chance, they “often become loyal, motivated and dedicated employees who contribute positively to their workplaces and communities.”

Donald Bowens, one of two job coaches at the St. Petersburg location, had similar thoughts.

“Everyone makes mistakes, but those should not define our future,” Bowens said. “Second chances mean helping individuals rebuild in a way that honors their potential, not punishes their past.”

Mental Health Services

During the Ready4Release program, participants meet with a mental health therapist. This is the third and final step in the process. When Davis speaks with clients, he emphasizes how important this aspect is for them. He also stresses that this is not to put them on medication, but to encourage conversations.

“Medication-first” approaches may turn people off to therapy.

“A reality that I express to them is that I think it’s impossible for them not to have some form of post traumatic stress disorder,” Davis said. “I think having a conversation with a specialist to make sure we have those understandings and give them the coping skills (is important). So, once they’re out and they’re in a job situation, they don’t revert back to a behavior that may force them to lose that job.”

He uses an example of someone who may have undiagnosed anxiety and works in a small warehouse. They have found a great job that offers them $20 per hour, but the confinement of the warehouse is starting to become a problem.

Davis explained that now, their anxiety kicks in and they revert to what they’ve always done, which causes people to be upset, scared or afraid. They lose their job, and someone else assumes the position.

He said if this individual had the mental health counseling they needed, they would be able to develop the coping skills required for this situation. They not only lost a job, but the employer also no longer trusts that their organization, ONH, is sending them quality people.

“I express the importance to them like this because if we don’t cross that T or dot that I, we do a disservice to them, and we do a disservice to the organization of what we’re trying to do,” Davis said.

An article by the American Psychological Association discusses the challenges incarcerated people face upon release. Social psychology refers to someone’s relationship to the world and those around them, and how that shapes individual beliefs and behaviors.

The APA describes the study of social psychology as “how social influence, social perception and social interaction influence individual and group behavior.”

Using social psychology to assess the situations that may have led to their incarceration, the APA discusses how this is reflected upon individuals after their release.

“From there, individuals walk into a world where the logistics can prove overwhelming— everything from finding a job and somewhere to live to keeping up with parole and avoiding the old neighborhoods, people and patterns that landed them behind bars in the first place,” the APA said. “This world also may be unrecognizable.”

Community Partnerships

ONH has created partnerships with organizations throughout Florida. The St. Petersburg campus has made connections with agencies in the Tampa Bay area to assist with their needs.

Davis described their community partnerships as traditional networking: phone calls, emails and conversations. He said that the ONH staff researches providers to see what they do and compare it to what ONH does not have, and from there they try to make a connection.

“It really was just making phone calls, having conversations, taking advantage of any public item we possibly can that we get an invitation to, whether it be myself, (or) whether it be the CEO,” Davis said.

He said that pre-release program managers are invited to reentry fairs, which are events held to allow partner organizations to hear 15-20 minute pitches about reentry programs offered locally.

The organizations can provide goods or services to a program, becoming one of their community partners. Davis said that even just hearing the offerings that other reentry programs provide inspires him.

The process at the fairs works like a meet and greet—Davis said they make connections based on interactions and meeting people. He said that it’s also a way for them to hold people accountable based on the services they say they are willing to provide.

“What we try to do is kind of hold people to what you say,” Davis said. “‘So, you say you hire people with criminal backgrounds. Well, we’ve got some good people.’”

Davis listed some of the Mount Zion Church and ONH partners. For food services, they’ve partnered with three pantries located near the church, as well as Feeding Tampa Bay. They have a few clothing providers, including thrift stores, Goodwill and UF Pasadena Health Floor. They also have a cellphone provider.

In addition to these partners, ONH has the support of state representatives and both Democratic and Republican leaders. These leaders also help fund the program. Because of their community partners, ONH can provide human necessities—what Davis said are “things that we take for granted on the other side.”

Program participants receive fresh meals, hygiene bags, a place to store food and clean clothing.

Davis advocates for fresh, healthy meals. Through partnering with smaller food vendors, they can provide lunch for program participants Monday through Thursday on Ready4Release career development training days. He illustrated that what they serve in correctional facilities can hardly be described as food.

“By doing it, I think we give them a slice of humanity back,” Davis said. “That you can enjoy a good meal. You probably haven’t been able to do that for, unfortunately, years.”

Government Impacts

The National Council of Nonprofits warned organizations about the government shutdown and the risk it poses to critical services.

According to their insights, “The longer a government shutdown lasts, the more severe the negative impacts; a long-term shutdown can significantly delay payments to nonprofit organizations, disrupt critical services, increase costs, reduce impact and make public-private partnerships less effective.”

Korey McDougald is ONH’s marketing and communications manager, located at their main campus in Jacksonville. He explained how the nonprofit operated during the recent 43-day government shutdown.

“The recent government shutdown did not impact Operation New Hope’s funding, as the majority of our support comes from state legislative sources with only a small portion tied to federal dollars,” McDougald said.

McDougald mentions “federal dollars” because some nonprofits rely on federal grants and contracts, according to the NCN. During a government shutdown, federal agencies cannot spend or allocate “congressionally approved funding.”

According to the NCN, government agencies “must stop all non-essential functions” during a shutdown. McDougald said that their clients were more heavily impacted compared to the organization.

“Our staff operations also remained unaffected. However, the shutdown did directly impact many of the individuals we serve,” McDougald said.

One main concern for ONH’s second chance citizens was the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, a federally funded program that provides food benefits to supplement individuals’ grocery budgets.

“Several of our clients experienced heightened uncertainty around SNAP benefits, which was especially concerning given the food insecurities they already face,” McDougald said.

Reflecting on the shutdown, McDougald said he is committed to maintaining a sense of stability for second chance citizens through ONH.

“While the shutdown has since ended, we continue to support our clients as they navigate these challenges and work to maintain stability for the remainder of the year,” McDougald said.

A poster mounted on the wall at Operation New Hope St. Petersburg reminds second chance

citizens to have hope through inspirational quotes. (Graphic by Emilie Bell)

ONH will continue to work with second chance citizens by empowering them to break the cycle of poverty and incarceration. They aim to reconnect them with the community and offer them stability. For more information on ONH, visit their website: https://operationnewhope.org/

“We work with these people every day, and they’re just like anybody else,” Davis said. “They’re trying to make the most out of time, the life that they have.”