By Jasmin Parrado

For the first time in almost seven years, Pinellas County began efforts this fall to renourish beaches eroded by an intense hurricane season last year, but it will do so without federal aid, which previously accounted for 65% of its costs toward the project.

The county first proceeded with the decision to fund the project in June, after it was unable to acquire permanent public access agreements, known as easements, from all property owners along its barrier islands.

Now, county government officials are concerned about what an incomplete nourishment project could mean for the safety of the beaches, as the project is only pumping sand for properties that signed easements.

“If we can’t put the full amount of sand on the beaches, then that’s going to really create and cause a lot of weak points,” said Zachory Westfall, geologist at Pinellas County Coastal Management.

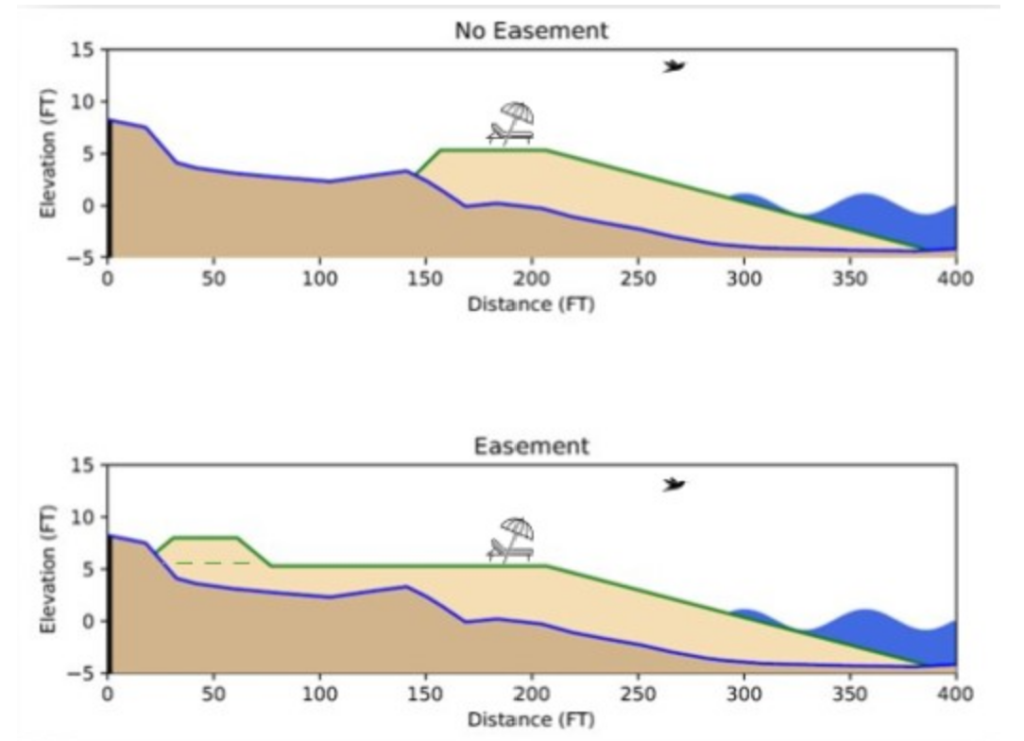

For properties that didn’t sign easements, sand won’t be leveled beyond what is called the erosion control line, a state-regulated line establishing what is public and private land in beachfront areas.

From a sand-volumetric perspective, the unnourished gaps of beach terrain can still invite the worst effects of surge and flooding from future storms, Westfall said.

Despite that danger, residents are still refusing to sign, and the county remains at an impasse with the federal government over its easement policy – which is required for fund provisions.

The issue first alarmed property owners across the county in 2022 when the United States Army Corps of Engineers, which usually covers a majority of expenses for beach nourishment, began strictly enforcing its policy requiring perpetual easements from 100% of property owners in the county.

Before that, property owners only had to sign easements granting temporary public access to some part of their land during construction for federal aid. Even then, they were divided on doing so, and all nourishment projects in the county were placed on hold.

Some residents signed with hopes of expediting the nourishment project and restoring the beaches while others didn’t budge, arguing that their homes didn’t need it or that they simply didn’t consent to public access.

The project isn’t physically built to work around the matter, Westfall said.

“We don’t just put sand out there, willy-nilly, and hope it’s okay,” he said. “These beaches are actually engineered in a certain way and have a certain width so that they can last long.”

While the policy turnover sparked years-long disagreements, Milan Mora, chief of the USACE’s Water Resources Branch, maintains that permanent public land access is necessary for federal participation.

Legislation from the Water Resource Development Act limits where federal project funding can be directed, prohibiting funds spent toward private property, he said.

Additionally, the USACE’s regulations state the main problem.

“In plain English, we, the federal government, in order to construct a project, need land,” Mora said. “The federal government cannot go in and arbitrarily start building something on a private property that nobody has given us the right to be on.”

The beach nourishment effort calls for consent to public access more than ever, Mora emphasized. For more than 50 years, the project was upkept through a cost-sharing period between federal and non-federal parties.

Even after this initial period ended, the project maintains a status of “operation and maintenance,” meaning that the county still renews it to ensure that beaches maintain their appearance and safety, wildlife recovers and tourists return to sandy shores.

“It’s on the hook to rehabilitate or restore the project in perpetuity if it’s damaged by a storm, a hurricane, in some cases a bad nor’eastern – anything that Mother Nature throws at the project,” Mora said.

Mora affirmed that the county must get every resident on board so that the USACE can work with a full, uninterrupted stretch of terrain to properly prepare beach dunes for future storms. But Pinellas County Commissioner Kathleen Peters doesn’t see that realistically happening anytime soon.

“People are not going to sign over their property,” Peters said. “Not in perpetuity.”

Peters recalled how some land portions that would become publicly accessible through easements bled into land property owners used – their pools, driveways and patios.

As she saw it, residents with that issue were never going to sign an easement consenting to permanent access to those areas.

“That’s why it’s an unreasonable policy interpretation,” Peters said. “People felt that it was a government land grab and that the federal government was trying to take their land from them.”

Like the USACE, Peters worries about the ineffectiveness of the project. Though the erosion control line at least gives some leeway for public access, there are still areas on private land that are vulnerable to erosion – areas that could even intensify erosion for properties that signed easements and were given extra sand.

“The neighbor that chooses not to sign is going to harm their neighbor’s property who did sign, because the water’s going to find those gaps and erode that more quickly,” Peters said.

Peters urges for the project’s completion, not only to upkeep pristine beaches for tourism prospects, but to save wildlife such as turtles and to secure the overall safety of residents.

That being said, the only solution Peters sees is a compromise with the federal government, one that she hopes can work independently of unanimous easement signatures she thinks are unlikely to happen.

The issue is not just happening in Florida. With states like New Jersey tackling a lack of federal funding for replenishment and California’s beaches also eroding, the conversation will escalate at one point or another, she believes.

“This is a national problem,” Peters said. “And it will also be a problem for lakes and rivers, not just the shoreline. We really need to come up with a resolution on the interpretation of this policy, because it’s not a law – it’s a policy.”

In the meantime, the 2025 Pinellas County Beach Nourishment Project is trying to reach as many residents as possible to secure easements, which are still being accepted and tallied as the effort continues.

Westfall, who primarily deals with contacting property owners about signing easements, is finding it difficult to reach everyone to begin with, as some properties are Airbnb homes or are run by property managers instead.

“So, we have to really track these people down somehow to try to just get the word out to them,”

Westfall said.

Westfall hopes that enough outreach can inform property owners of how vital the project is, especially as negotiations with the USACE remain at a standstill and the clock ticks toward future weather systems.Out of 475 properties, 227 have currently signed easements compliant with the USACE, and 148 out of 180 properties have signed temporary easements.

Pinellas County reports that sand placement is ongoing in Sand Key; it is currently stationed in Clearwater Beach and Bellair Beach. Nourishment will also ensue in Treasure Island and Upham Beach as the project develops.